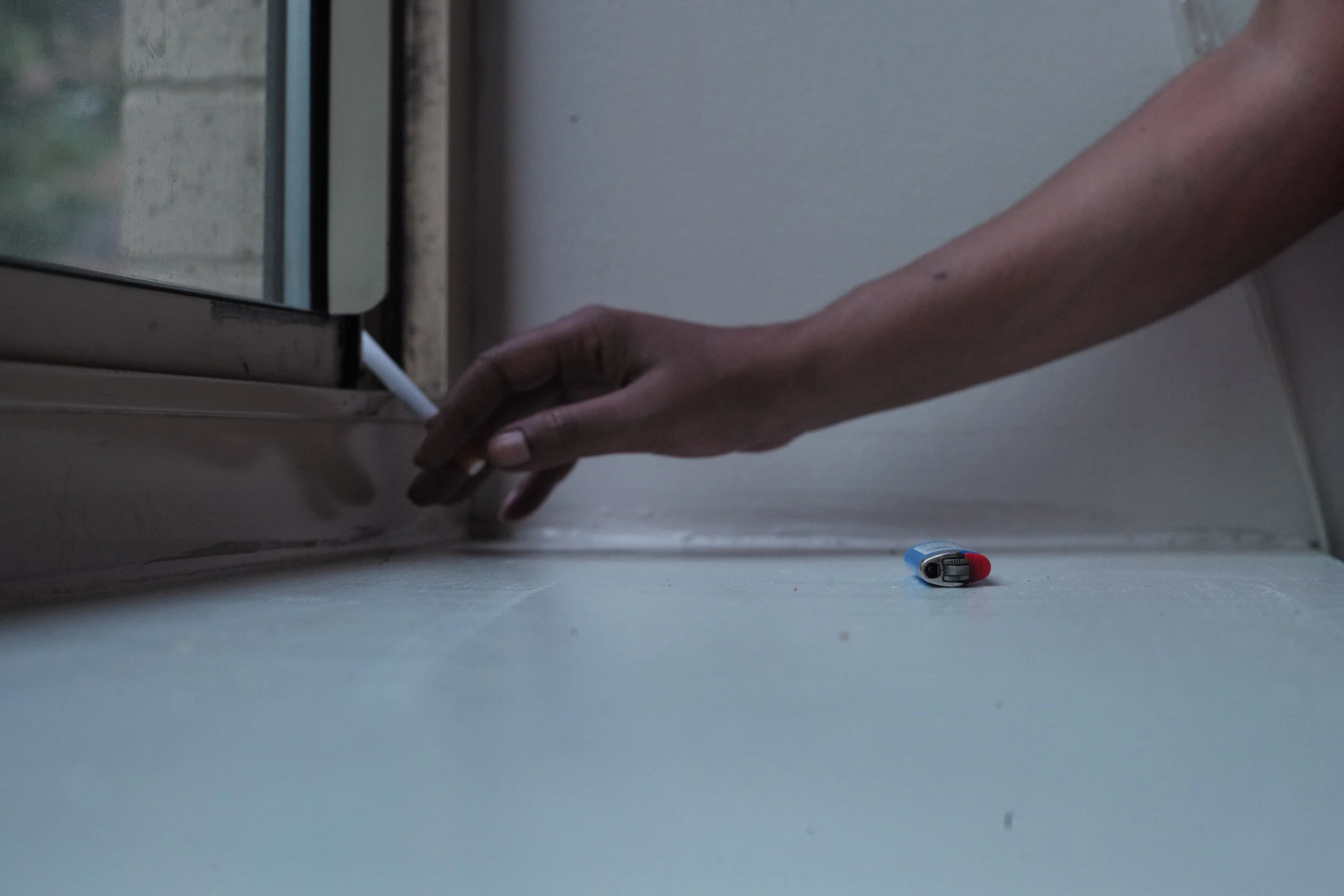

I went to visit my boyfriend at the beautiful Hopital Ferdinand Widal near the Garde Du Norde. He snuck out for a coffee. Fifteen minutes later he gasped at the time—my favorite expression of his— and left. I stayed on to pay the tab.

A woman at the bar saw me struggling with my cane and asked if she could help. I was more concerned about looking like a disheveled, homeless, drunk with my holey clothes and lack of balance which results in a kind of swagger that can be open to all sorts of interpretations. I know this after a someone spotted my cane handle sticking out of my coat pocket and thinking it was a weapon called the police on me.

The woman and I got talking and eventually drinking. A sweet Hungarian girl who kept insisting I must go to Cannes and defend my work which will be premiering there later this week. I was uncertain because I wasn’t feeling well.

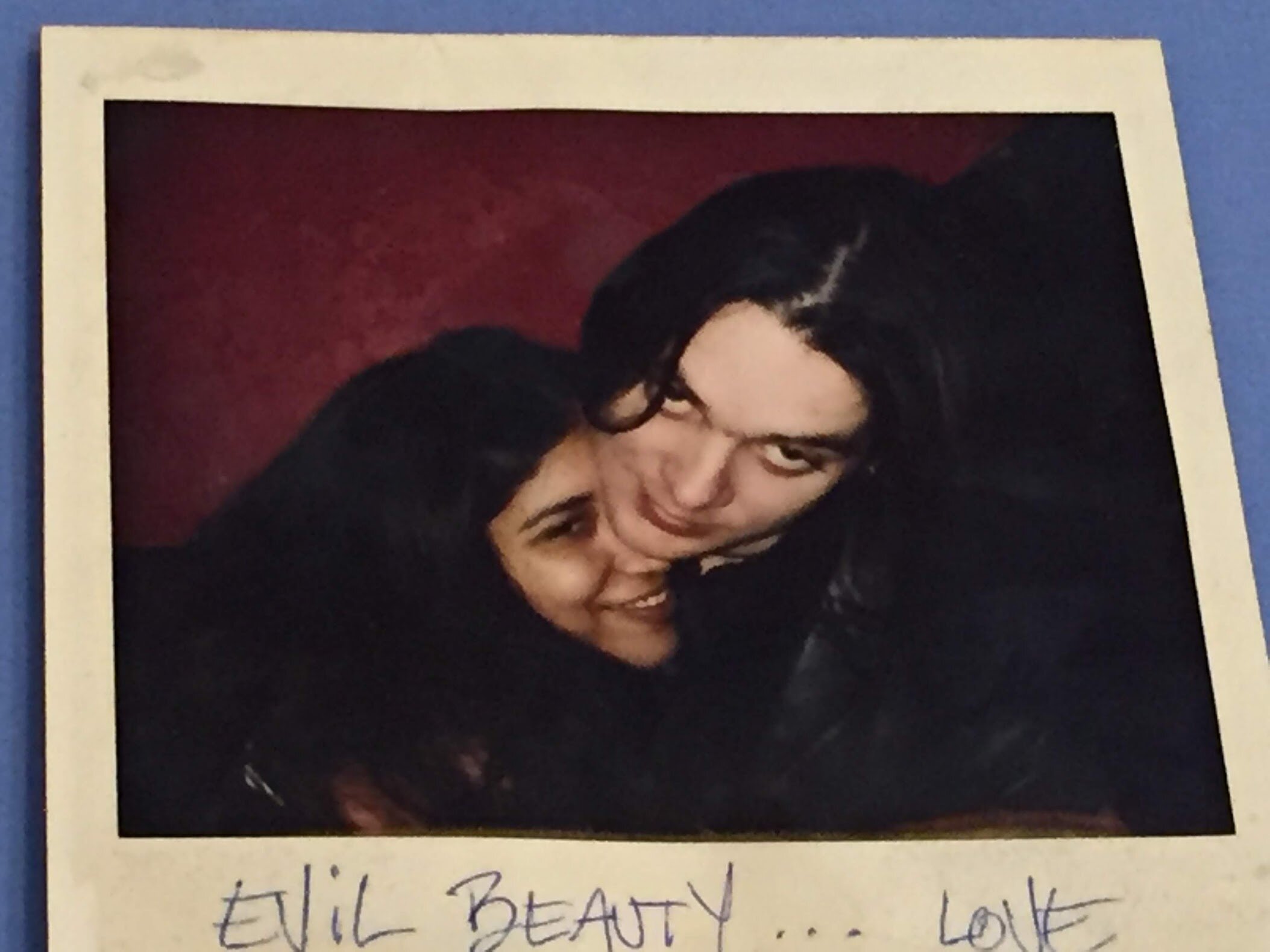

An hour passed, I’m quite sure of it, when I heard a voice out on the street. ‘Excuse me, are you Buku Sarkar?’

I was sure this was another rendezvous with the Paris police.

Instead, I found myself facing two young Indians- a girl and a boy.

‘I told you it was her,’ he said to his companion.

I’m sitting with my wine and my new Hungarian friend, quite stupefied. She was staring at me, even more so, wondering what celebrity did she pick up in at the busy, slightly worn off cafe by the trash around Gare du Nord.

‘We love your work,’ the boy gushed.

‘Yes,’ his female companion concurred.

‘Vishal from Asia Stories turned me onto to your bodies work to study,’

I’m still listening, or half listening, thinking the mantra of the day (you never know what surprise waits for you outside if you can only manage to make the day begin) actually worked.

They were film students it turned out but as I have come to know these days, like all film people, also aspiring photographers.

I invited them to join our table. The boy told me where to get Indian street food and said it was actually very good.

Over my third glass of wine— the exact moment when I turn into my mother— the boy, a Bengali but from Delhi, showed me some of his work.

He showed me an image and said it was the most important thing he’d ever captured.

‘Why?’ I asked. Was it the bicycle at the corner of the frame?

‘No, actually the half sunk palm tree,’ he replied.

What is it about the palm tree? I asked.

He couldn’t answer.

It made me circle back to my musings off late about why visual artists are very ineloquent and inarticulate. I don’t mean this in a derogatory manner. I have seen this in myself too. Images are a more primate way of expression than words. It’s more instinctive. A reaction. Science will tell you images comes from the same part of our brain where a child learns to associate objects with names, alphabets.

Words require a discipline of turning that impulse into coherence. Images explore what words cannot explain and yet I am convinced that if one cannot articulate what they are doing, they will never reach their fullest potential as an image maker.

Over the fourth wine, I told him this:

Drink a couple of beers, wine. Get a little tipsy. Stare at the image and write unabashedly like a young boy in love, having read Rilke for the first time. No one will see these words, I assured him. They were wholly his secret failures. . ‘But’, I said, you will find in those embarrassingly, gushy words, the kernel of the idea you were trying to capture in this image.

Keep at it and one day you’ll be able to talk about your work to an important curator or a magazine with a confidence that only comes from deep understanding. The kind of confidence where you abandon jargons and ‘isms’ for plain, simple, child like language (which mind you is the hardest way to write). The more confident you are, the less you’ll need to show off in vocabulary.

It is important, if only privately, to be articulate about what you are doing and why. As an artist, of any discipline, you have to be able to answer your own quetsions. Or work towards an answer. Taking a photograph is easy. We can all do it. But to analyze it, rationalize it (yes, as counterintuitive as it feels) is as important as taking the image itself. How else will you grow?

Don’t just pass it off with the ‘image speaks a thousand words’ nonsense because we only say that out of defensiveness.

You know this is true.

So there, in a cafe, amidst hordes of Indian restaurants and the train station, I spewed my teacherly advice. And I realized how much I loved doing so.

I’ll be teaching at a variety of classes this summer so do sign up on ny newsletter to get news.

Try it though- anywhere. Look at your favorite image, let go of your inhibitions with a glass of alcohol, and write in the silliest, most pretentious language what the image means to you. No one will see it but you. No one will judge it. But I promise you, a deeper journey with your work will commence.